PMJAY’s Design Problem

By Arunima Rajan

When Universal Health Coverage Meets Fiscal Reality

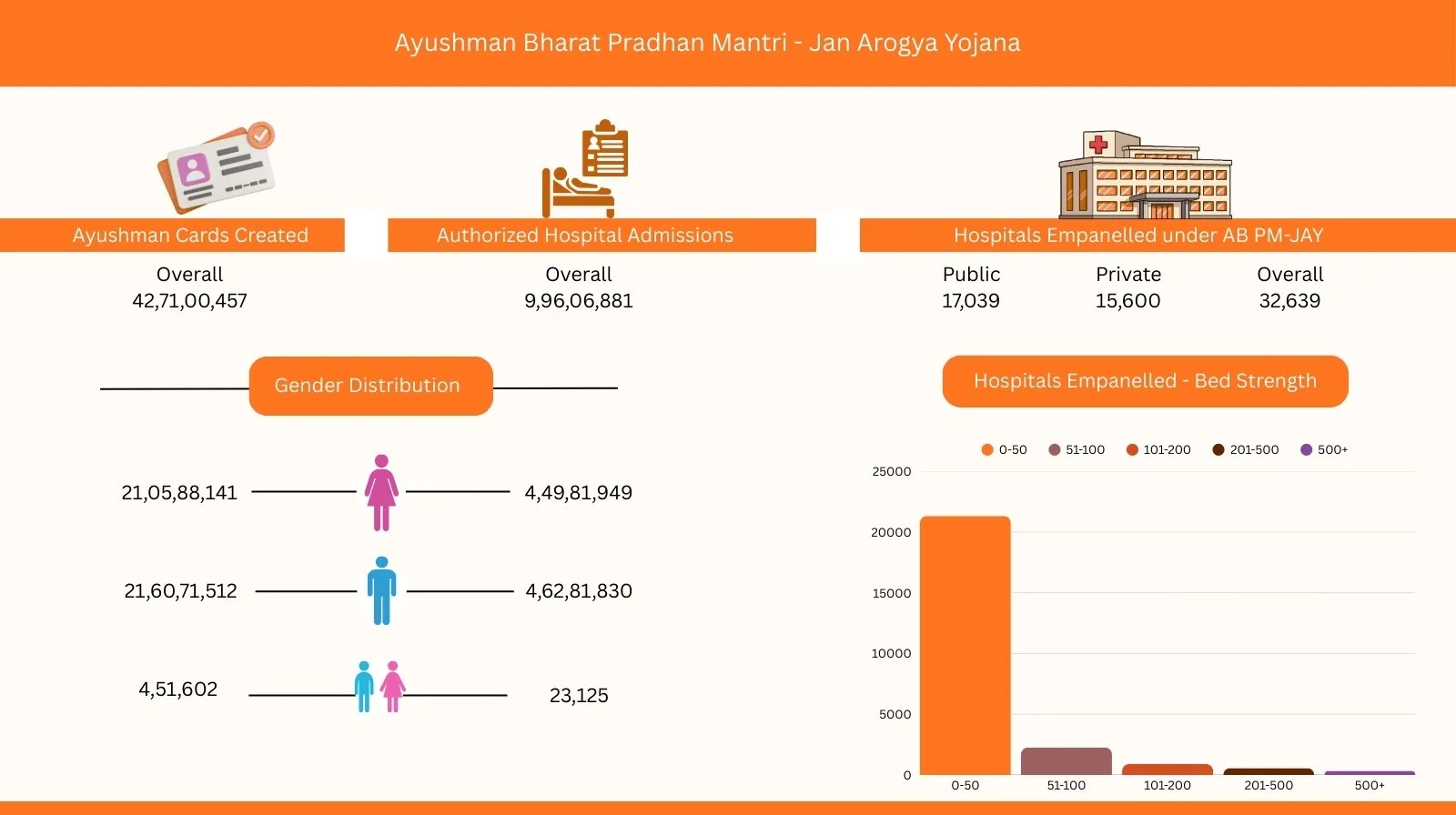

Universal Health Coverage Day passed quietly on December 12, but it offers a timely opportunity to ask a fundamental question: how is the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) really performing?

Launched in 2018 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, PMJAY was framed as a historic leap toward universal health coverage. The promise was ambitious: ₹5 lakh per family per year in health insurance. This was particularly transformative for low-income and middle-class households historically excluded from formal health insurance.

Seven years on, however, the scheme continues to struggle with a persistent tension between ambition and fiscal reality.

Universal Health Coverage: A Democratic Imperative

According to Girdhar Gyani, Director General of the Association of Healthcare Providers India (AHPI), universal health coverage is not merely a policy choice but a democratic obligation.

“Education and health are two core responsibilities of the state,” Gyani notes. “Governments are expected to ensure basic education and access to healthcare for all citizens.”

Universal health coverage, he explains, is fundamentally about affordability. Healthcare must be free for those below the poverty line, while subsidies can taper progressively for higher-income groups. Wealthier citizens, by definition, do not require state support.

Gyani brings deep institutional experience to this perspective. Prior to joining AHPI, he served as Secretary General of the Quality Council of India (QCI) from 2003 to 2012, where he played a pivotal role in embedding quality standards into India’s regulatory frameworks across healthcare, education, industry, and public services.

From State Experiments to a National Framework

PMJAY did not emerge in a vacuum. Several states had already experimented with publicly funded health insurance. Andhra Pradesh’s Aarogyashri scheme, launched in 2007, was followed by similar initiatives in Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Gujarat.

However, PMJAY consolidated these fragmented efforts into a single national framework.

Under the scheme, eligible families receive ₹5 lakh in annual health coverage. Funding follows a 60:40 split between the Union government and states, making PMJAY one of India’s most expansive centrally sponsored welfare programmes.

Coverage Gaps Beneath the Headline Numbers

Eligibility is determined using the Socio-Economic Caste Census, which identifies vulnerable groups such as households living in kutcha houses (a basic, temporary dwelling), Scheduled Castes, female-headed families, and other disadvantaged categories. Together, these groups account for roughly 40 per cent of India’s population.

Yet implementation remains uneven. “Even today, many eligible beneficiaries especially in remote and underserved regions have not been issued cards or brought into the system,” Gyani points out. “A small but significant population remains excluded.”

The Fiscal Constraint

At the heart of PMJAY’s challenges lies a simple but uncomfortable truth: insufficient funding.

Globally, countries spend an average of about 9 per cent of GDP on healthcare. In India, government spending remains below 2 per cent of GDP, with the private sector contributing an additional 2.5 per cent . Even combined, this 4.5 per cent is inadequate to provide comprehensive healthcare for a population of India’s size.

“With limited public funding, the government is attempting to cover 40 per cent of the population,” Gyani explains. “The result is inevitable delayed reimbursements.”

Payments to hospitals are frequently staggered, delayed by three to six months, and in some cases up to a year. These delays stem from both fiscal constraints and systemic inefficiencies.

Gyani argues that discipline can be restored through a simple mechanism: reintroducing interest penalties on delayed payments. “A clause providing for 1 per cent monthly interest on delayed reimbursements existed when PMJAY was announced in 2018 but was later removed. Bringing it back would impose accountability.”

When States Overextend

Political incentives have further complicated the scheme’s finances. Several states have expanded PMJAY coverage well beyond the original 40 per cent threshold. Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, for instance, now cover nearly 90 per cent of their populations.

However, the Centre’s financial contribution remains capped at the originally eligible cohort. The additional burden falls entirely on states already struggling with limited fiscal space, exacerbating reimbursement delays.

This strain has provoked open resistance. In Haryana, nearly 650 private hospitals empanelled under the scheme threatened to suspend PMJAY services over unpaid dues exceeding ₹500 crore. The Indian Medical Association (IMA)’s Haryana chapter formally warned that hospitals would stop treating PMJAY patients unless pending payments were cleared.

The situation raises a larger question: does India truly treat healthcare as a national priority? While infrastructure, defence, and transport projects receive sustained investment, healthcare spending remains persistently modest.

“At the very least,” Gyani argues, “government health expenditure must rise to 2.5 per cent of GDP. Without that, no meaningful reform is possible.”

Fraud, Design Flaws, and Technology Gaps

Fraud has emerged as another major concern. According to the Ministry of Health, over 3,100 hospitals have been found guilty of irregularities since PMJAY’s inception. More than 1,100 hospitals have been de-empanelled, penalties worth ₹122 crore imposed, and hundreds suspended.

The government has attempted to address this through the National Health Claims Exchange (NHCX), a digital platform designed to provide real-time visibility into treatments and claims. Gyani believes the tool has significant potential but only if universally adopted.

“Making NHCX mandatory across hospitals and insurers would dramatically reduce fraud and administrative friction,” he says.

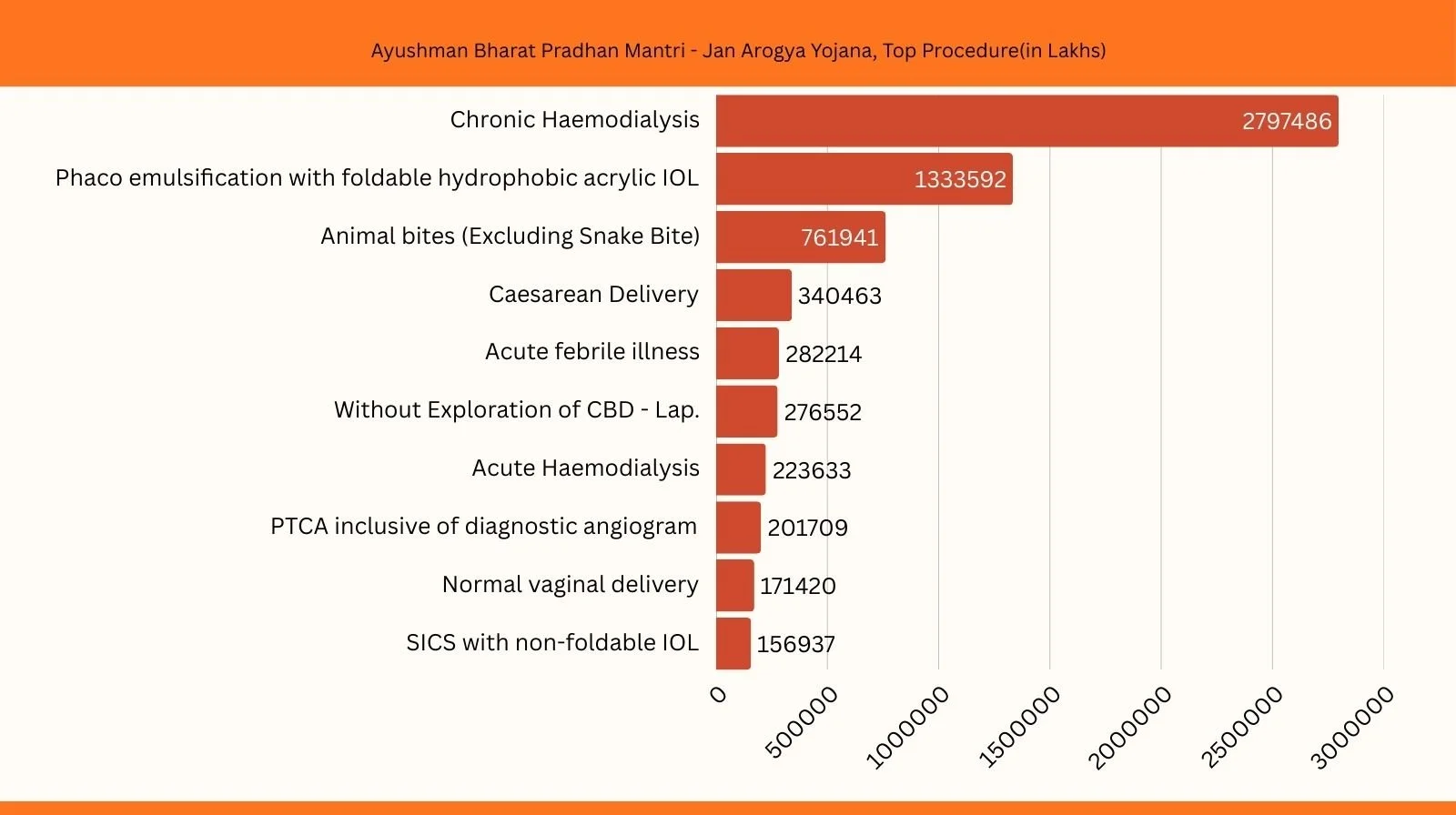

Yet technology alone cannot fix flawed empanelment. Many small nursing homes lacking adequate infrastructure are empanelled by state agencies, increasing the risk of misuse and collusion. Compounding the problem are reimbursement rates that often fail to cover basic operating costs, pushing hospitals toward shortcuts or discouraging participation altogether.

Rethinking Empanelment Through Accreditation

Directly auditing thousands of hospitals is neither practical nor effective. Gyani proposes a more sustainable solution: mandatory quality accreditation.

“Every hospital seeking PMJAY empanelment should have at least entry-level certification from the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers (NABH),” he argues.

NABH already has the auditor capacity to ensure compliance, while the government can retain oversight. This approach mirrors international best practices such as the requirement for Joint Commission accreditation in the United States.

Although accreditation entails costs, entry-level NABH certification is affordable and could be subsidised by the government. Given that NABH operates under the Quality Council of India, such a move would improve patient safety, reduce fraud, and enhance trust in the system.

The Risk of Private Sector Exit

India’s rising life expectancy from about 37 years at Independence to over 73 years today—owes much to advances in healthcare. But these gains come at a price. Medical technology is expensive, specialist talent is scarce, and much equipment is imported.

“If reimbursement rates remain unviable and payments unpredictable, private hospitals will continue to opt out,” Gyani warns. “That would severely restrict access to complex and tertiary care under PMJAY.”

He suggests that introducing co-payments, at least under schemes like the Central Government Health Scheme or CGHS, could help bring high-quality hospitals back into the fold.

The Bottom Line

On paper, the government can claim that nearly 70 per cent of Indians have some form of health coverage through PMJAY, private insurance, CGHS, the

Ex-Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme (ECHS), or employer-sponsored schemes. On the ground, however, PMJAY’s impact remains uneven.

“Many empanelled hospitals do not actively treat PMJAY patients,” Gyani concludes. “Until structural issues around funding adequacy, pricing realism, accreditation, and payment timelines are addressed, out-of-pocket expenditure will remain high and quality improvements limited.”

PMJAY’s promise remains compelling. Its design flaws, however, underscore a deeper truth that universal health coverage cannot be achieved on ambition alone it requires sustained political, fiscal, and institutional commitment.

Got a story that Healthcare Executive should dig into? Shoot it over to arunima.rajan@hosmac.com—no PR fluff, just solid leads.