India’s Fight Against AMR: Awareness, Surveillance and Stewardship Hold the Key

By Arunima Rajan

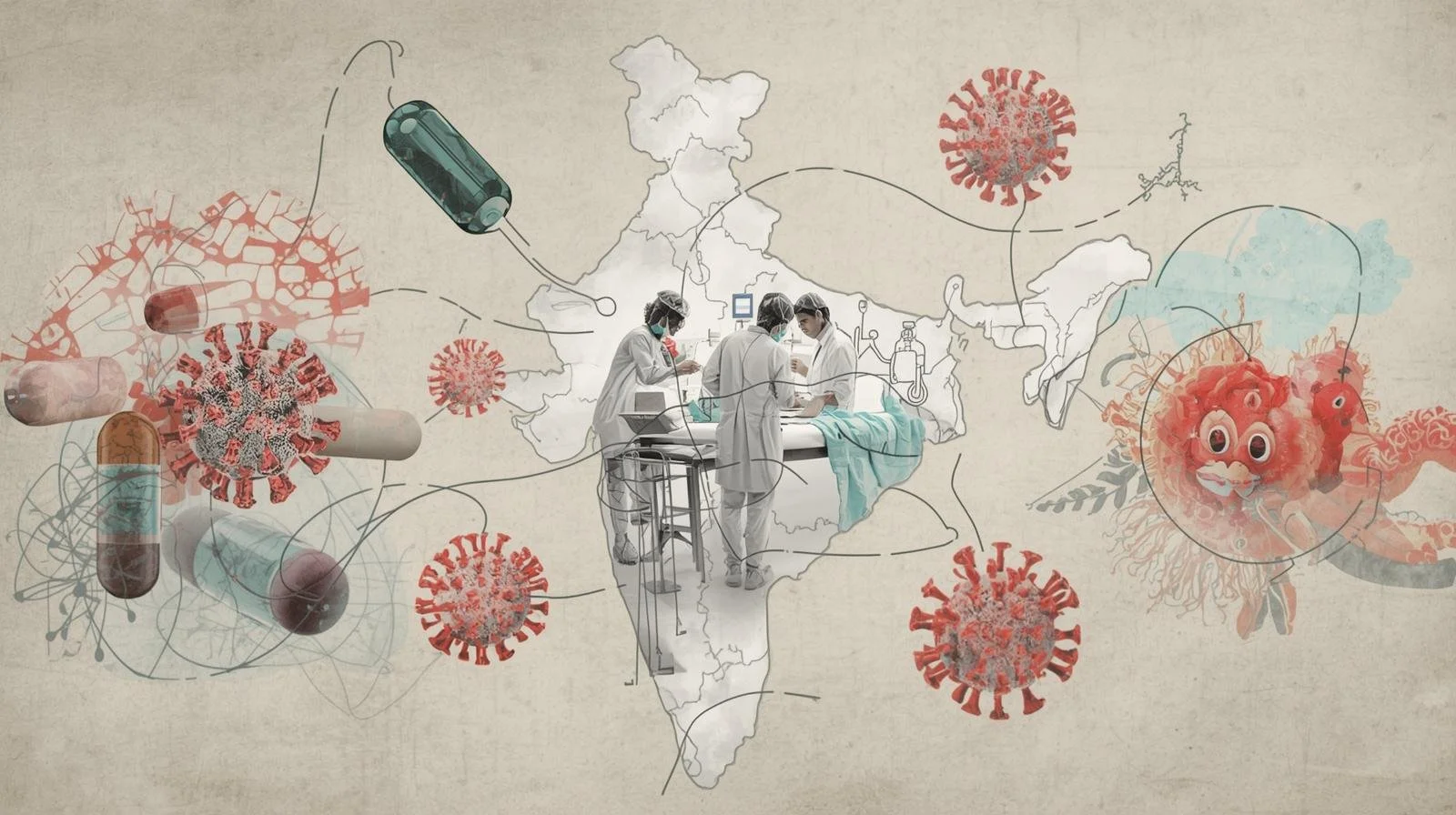

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) cannot be addressed by managing hospitals alone. It is an interconnected web of humans, animals and the environment.

The AMR crisis is unfolding in slow motion, largely out of public view and trapped in academic silos. In India, it increasingly resembles the script of a disaster movie. No longer ignorable, the country is fast becoming ground zero for drug-resistant infections.

The neighbourhood pharmacist who dispenses antibiotics without a prescription, poultry farms that routinely feed antibiotics to chickens, and patients who prefer pharmacies over primary care physicians are not isolated behaviours. They are cogs in the same wheel. The consequences surface quietly in hospitals: a premature baby in a neonatal intensive care unit battling sepsis, and doctors struggling as the weapons in their arsenal fail.

Addressing this crisis requires a coordinated battle plan that brings together healthcare providers, regulators and patients and pushes the AMR discourse into the bloodstream of the nation.

Priya Nori, Professor of Medicine (Infectious Diseases) and Orthopaedic Surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, serves as Medical Director of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme (ASP) and Outpatient Parenteral Antibiotic Therapy Programme (OPAT), and is Co-Chair of the Antimicrobial Council at Montefiore Health System.

Based on her research and clinical experience, Nori says the evidence practice gap is widest in three areas:

Overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics for patients who meet sepsis criteria despite having little risk for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs), such as those without recent antibiotic exposure or healthcare contact. This is commonly seen in intra-abdominal infections, community-acquired pneumonia, and febrile urinary tract infections with leukocytosis.

Reluctance to shorten antibiotic courses, despite strong evidence that “shorter is better.” Diagnostic uncertainty, lack of positive cultures, and a “just-in-case” mindset often drive unnecessarily prolonged treatment.

Knowledge gaps around IV-to-oral equivalency, with many clinicians continuing intravenous therapy even after clear clinical improvement, despite robust evidence supporting oral treatment.

Financial drivers often shape the translation of research and policy into hospital and patient practices. Rapid infectious disease diagnostics have expanded dramatically since COVID-19. Home testing for sexually transmitted infections, for instance, has grown rapidly, a positive development for public health.

However, Nori cautions against indiscriminate use of multiplex diagnostic platforms. “When applied to conditions like urinary tract infections, excessive information can confuse clinicians and lead to overtreatment, particularly of asymptomatic bacteriuria, further driving AMR.”

Political Momentum and a Growing Crisis

Recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi highlighted India’s AMR crisis in Mann Ki Baat, calling it a serious public health concern. This high-level acknowledgement has created political momentum, but what policy levers must India pull next to convert awareness into action?

One of the Highest AMR Burdens Globally

“The situation is extremely grave,” says Dr Ranga Reddy, President of the Infection Control Academy of India. “India faces one of the highest AMR burdens globally.”

Referring to the latest ICMR-AMRSN data cited by the Prime Minister in December 2025, Reddy notes that antibiotics are increasingly ineffective against common infections such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections and typhoid.

ICMR’s 2023 report, whose trends extend into 2025 discussions, shows rising resistance in key pathogens. For example, Klebsiella pneumoniae susceptibility to imipenem has declined sharply since 2016, while carbapenem resistance is high in E. coli, Klebsiella, Acinetobacter and Staphylococcus aureus. Multicentric studies between 2017 and 2022 confirm growing multidrug resistance in both hospital- and community-acquired infections, resulting in prolonged hospital stays, higher costs and preventable deaths.

Ground realities such as overcrowded hospitals, self-medication and antibiotic overuse accelerate this spread. “The most concerning driver,” Reddy says, “is irrational antibiotic use over-the-counter sales, incomplete courses and empirical broad-spectrum prescribing compounded by weak infection control and diagnostic gaps that force defensive prescribing.”

What Policy Levers Should India Pull?

According to Reddy, the Prime Minister’s public acknowledgement is a game-changer: but swift, measurable implementation must follow.

Under the National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (NAP-AMR 2.0, 2025–2029), India should prioritise:

Tighter regulation of antibiotic sales: Strict nationwide enforcement of Schedule H1, digital tracking, pharmacist accountability and narcotics-like controls for critical antibiotics to eliminate OTC access.

Stronger stewardship frameworks: Mandatory antimicrobial stewardship committees in all public and private hospitals, with audits, feedback and facility-specific guidelines.

Robust One Health coordination: Operationalising the cross-sector approach across human health, animal health, agriculture and the environment through state AMR cells and inter-ministerial collaboration.

Greater investment in surveillance and research: Expanding ICMR’s AMR surveillance networks beyond tertiary centres, funding rapid diagnostics, and incentivising R&D for new antimicrobials and vaccines.

“Immediate impact will come from regulation and stewardship in human health, while One Health approaches ensure long-term sustainability,” Reddy says.

Beyond Awareness: Systemic Interventions

Public messaging, such as the Red Line initiative and appeals from national leaders, is necessary but insufficient.

“Experience from stewardship pilots shows that entrenched behaviours change only through multifaceted, systemic interventions,” Reddy explains. These include:

Embedding AMR and rational prescribing in medical, nursing and pharmacy curricula.

Integrating stewardship into hospital workflows through pre-authorisation, real-time audits and prescriber feedback.

Building accountability via performance metrics, peer review, incentives and penalties for overuse.

Enforcing community-level measures, including pharmacist training and patient education on completing antibiotic courses.

Non-Negotiables for Hospital Leaders

For hospital leadership, AMR stewardship must be non-negotiable. This includes multidisciplinary stewardship teams, prescription audits, restrictions on last-line antibiotics, and strong infection prevention and control (IPC) protocols.

IPC indicators, such as hand hygiene compliance above 90% and low healthcare-associated infection rates, should be treated as core leadership metrics, on par with financial performance and clinical outcomes.

“Prevention is by far the most cost-effective strategy,” Reddy notes. WHO benchmarks suggest effective IPC can prevent up to 70% of healthcare-associated infections. Hand hygiene programmes alone can prevent half of avoidable infections while delivering economic returns many times the investment.

The Evidence-Practice Divide

Despite extensive discussion in academic and policy circles, a large gap remains between scientific consensus and real-world practice.

Dr Vishwa Mohan Katoch, former President of the Department of Health Research, argues that AMR is often mischaracterised as a behavioural problem. “Doctors and patients are partially responsible, but the real issue is the lack of practical, dynamic evidence that applies to peripheral clinics and small hospitals.”

Guidelines, he says, are often static, poorly adapted to local resistance patterns, and insufficiently supported by diagnostic infrastructure. Without convincing, real-world evidence, behavioural change is difficult.

Lessons from Polio, TB and Leprosy

India’s success in eradicating polio and controlling leprosy offers lessons, but AMR presents a far more complex challenge due to the sheer volume of common infections and decentralised care.

“Evidence-based policy is the only viable path,” Katoch says. “We need large-scale, action-oriented implementation research to create models for rational antibiotic use across all levels of care.”

If India Could Do Just One Thing

If India were to prioritise a single structural intervention, Katoch suggests enforcing prescription-only access to critical antibiotics using AI-enabled monitoring systems, alongside strong investment in implementation research.

“Guidelines must be dynamic, grounded in Indian realities, and convincing to clinicians and patients alike. Only then will they drive real behavioural change.”

Got a story that Healthcare Executive should dig into? Shoot it over to arunima.rajan@hosmac.com—no PR fluff, just solid leads.