Can India repeat China's success with gig workers in community health?

By Arunima Rajan

The community health worker system suffers from a lack of understanding, lack of investment and lack of the strong will to make some basic health services accessible to all.

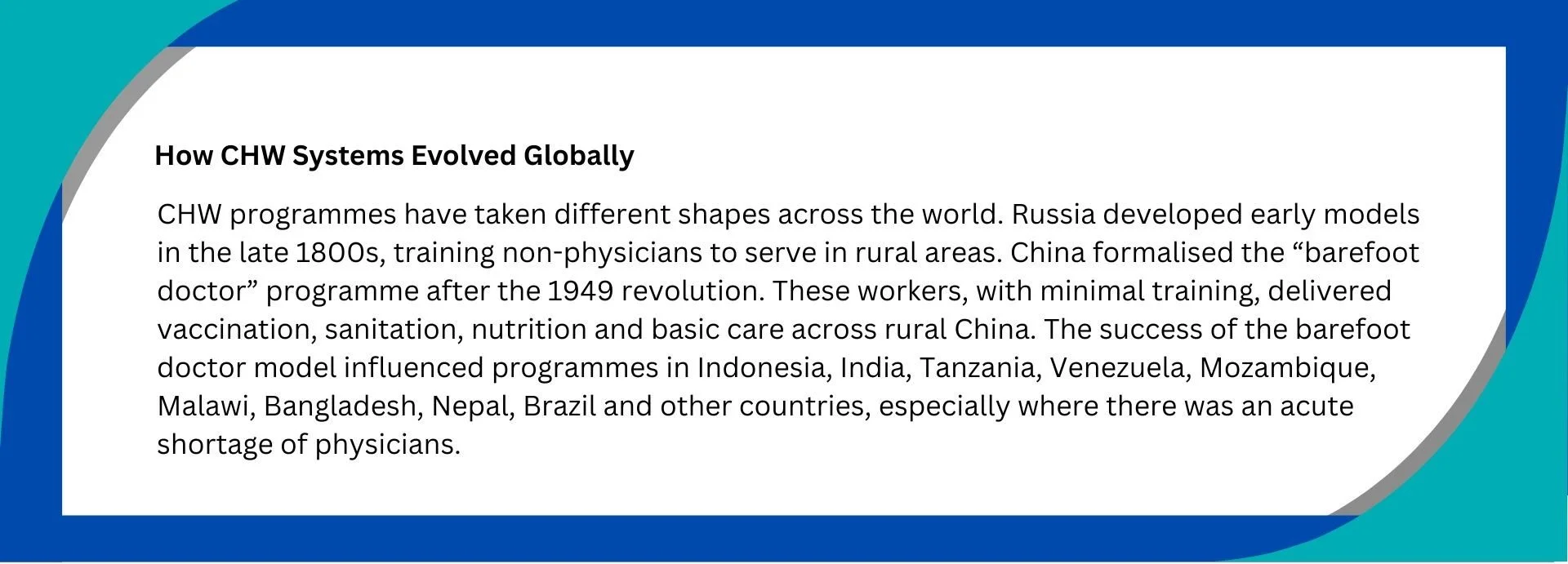

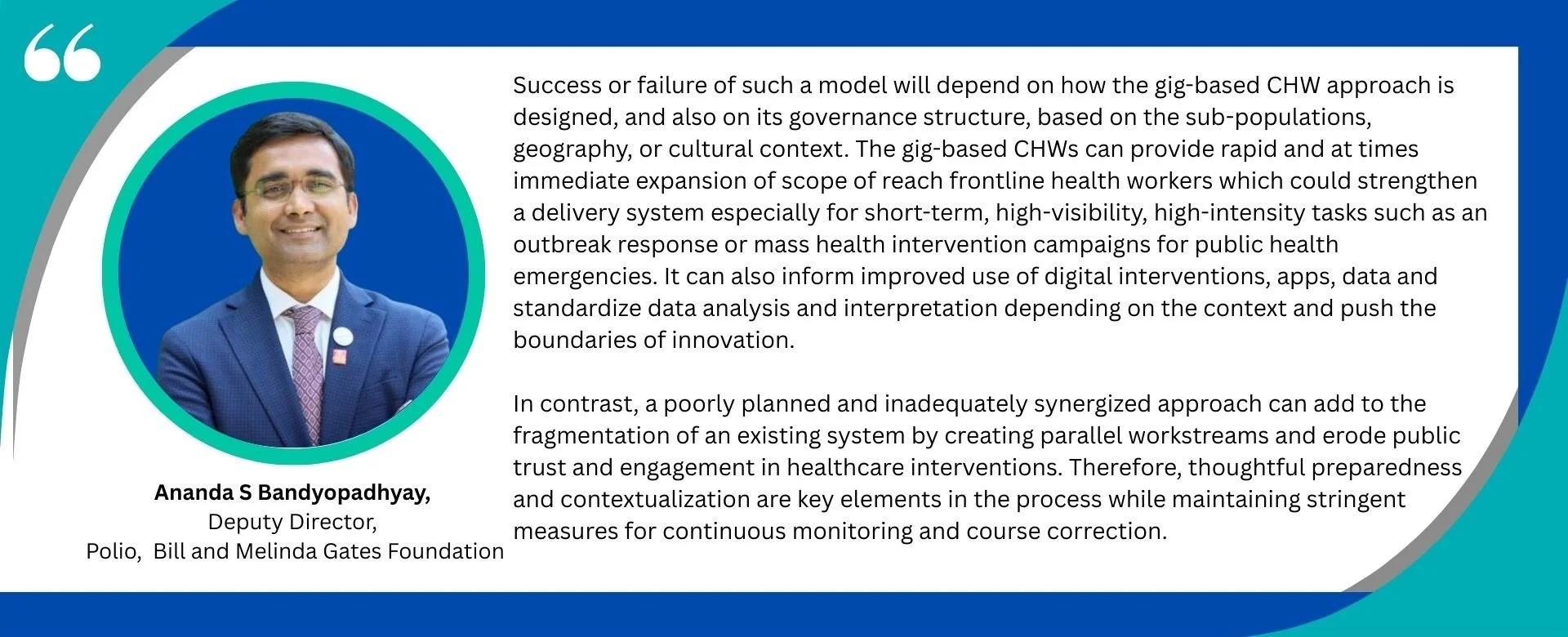

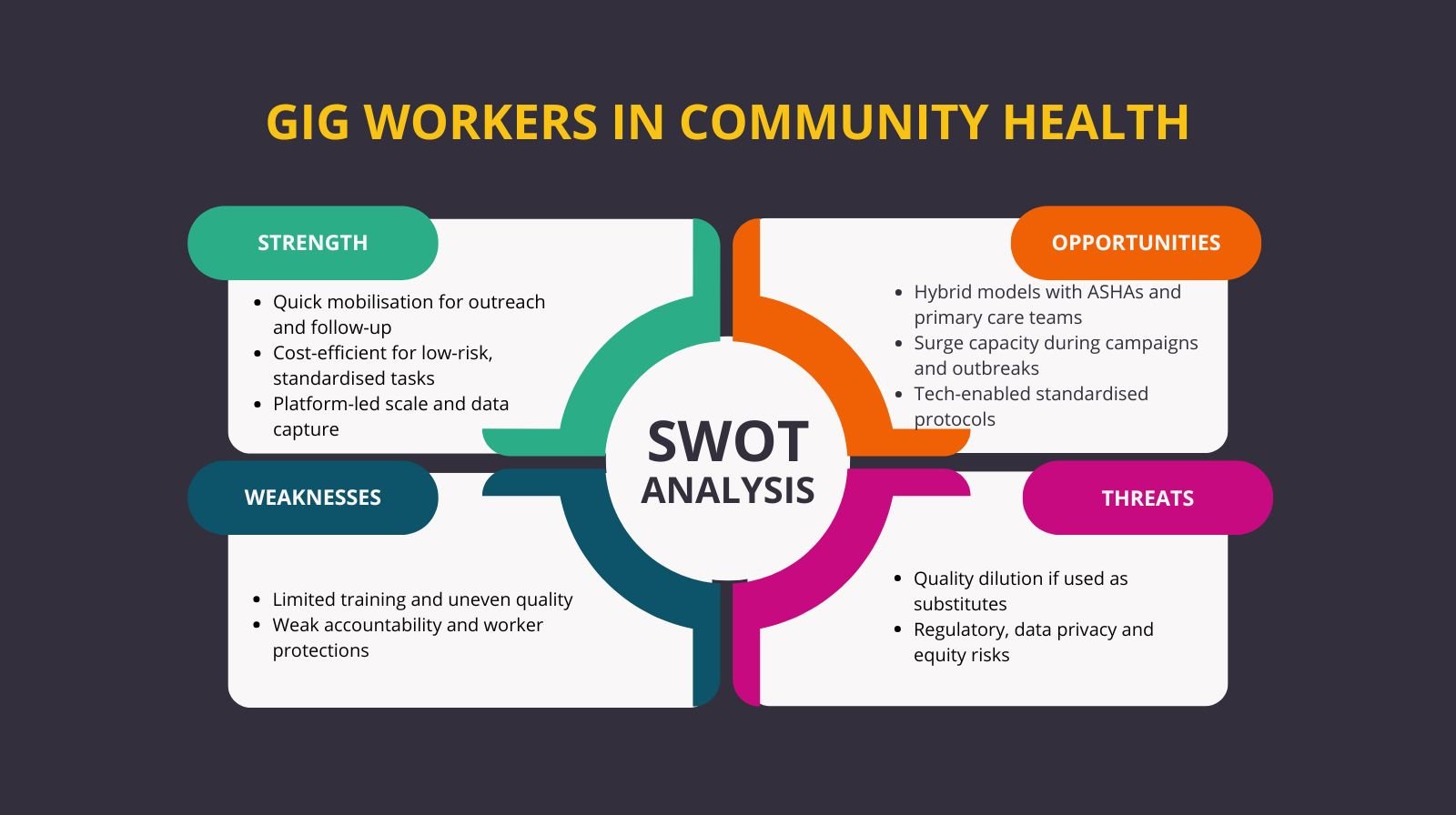

China's success in harnessing its vast gig workforce to bolster community health services, such as training delivery persons to ferry medicines, collect diagnostic samples and check in on vulnerable residents, holds lessons for the rest of the world. It presented a possibility for other countries grappling with public health systems that struggle to cater to the masses. Can an informal, fast-moving labour force fill the gaps in strained public health systems? Can India do this with its community health workers?

Marisa Miraldo, Professor of health economics and policy, Imperial Business School.

“China’s experiment with gig-based community health workers (CHWs) is intriguing because it doesn’t invent community health work so much as ‘Uberise’ parts of it,” says Marisa Miraldo, professor of health economics and policy at Imperial Business School.

“The safest way to view this model is as a complement, not a replacement. Gig workers are best used for modular, low-risk, well-protocolised tasks (e.g. outreach, data collection, follow-up reminders, last-mile delivery or short-term campaigns) while trained CHWs, ASHAs, ANMs and primary care teams remain responsible for ongoing, high-stakes, relational care. Whether China’s approach is truly scalable elsewhere is highly context-specific: it rests on strong digital infrastructure and significant state capacity to regulate platforms and data. For countries like India, the opportunity is a regulated hybrid – borrow the flexibility, data and reach of platform-based labour, but keep public-sector and community-based workers at the core, so that innovation in workforce models does not come at the cost of quality, equity or decent work,” explains Miraldo.

Community health workers (CHW) are community members who work for free or for payment and offer primary healthcare services to their community.

Dr Feroz Ikbal, Associate Professor, School of Health Systems Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

Dr Feroz Ikbal, Associate Professor, School of Health Systems Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai thinks India should try this model. "In the past few years, India has been trying to build a structure to enable health services to reach the last mile. One of the major challenges is to build a strong work force at the ground level. For example, one of the major challenges is to provide basic diagnostic services for NCDs. Gig workers can be trained to take the samples from households to labs. Many of our national health programs involve supply of medicines and healthcare goods, such as the delivery of TB medicines. Also, India is urbanising speedily. Maybe the next census will reveal that at least 60 % of Indians live in urban areas. Since gig workers are largely concentrated in urban areas, they can be used for some of the health service delivery activities,” says Ikbal.

What Community Health Workers Do

Poonam Muttreja Executive Director, Population Foundation of India

Poonam Muttreja is the executive director of Population Foundation of India. She notes that community health workers are a bridge between the public health system and the community. "Women health workers, who are familiar with the social norms, can be more persuasive than any doctor or hospital and help families arrive at health decisions. They can reach those

that the system frequently ignores, such as women, adolescents and marginalised communities, which is crucial in a nation as big and unequal as ours. Their work involves not just providing services but also building trust in the health system and guaranteeing that everyone is treated as a rights-holder, regardless of where they reside. Investing in them is an investment in ensuring a stronger health system and crucial to achieving universal health coverage," she says.

Modern Perspectives on CHWs

According to Karen L. Fortuna, Assistant Professor of Community and Family Medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, USA, developing countries can adopt models that employ CHWs to provide non-clinical, community-based care, similar to how it was done in China. "If we think about how healthcare actually happens, it doesn’t occur just during a 15-minute appointment scheduled months in advance. Most health, recovery and well-being occur outside the 15-minute appointment in the community. CHWs are the interstitial workforce operating between formal clinical care and everyday life in the community, where health is actually shaped. We need to empower patients outside the traditional healthcare clinic so they can take care of their own health. CHWs are ideal for this role because they are embedded in the community, have the time to provide support, and represent a workforce that can be scaled to meet growing need," she says.

She believes this model worked in China largely because it emerged in response to a real and urgent need. "Often, the most creative solutions come about when existing approaches aren’t working, and there are few options left. In those moments, systems are more willing to try something new — even ideas that might have seemed unconventional at first — and that rare moment of openness to "wild ideas" can create space for innovation,” she adds.

India’s CHW System

India has an existing community health workforce called Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) workers. ASHAs are female CHWs trained to function as a bridge between the community and the public health system. They were designated as community-based health functionaries under the National Rural

Health Mission launched in 2005. Women selected to be ASHA workers undergo multiple healthcare training programmes which enable them to do their role.

Ravi Duggal, Public Health Researcher

Concerns about Gig Workers

Public health researcher Ravi Duggal is cautious. “I have no issues with gig workers becoming link health workers but they can't be a replacement for a robust primary health care system. When India first adopted the barefoot health worker model from China in the Seventies it not only diluted the Chinese version in terms of skills but reduced investment in building proper primary healthcare. Every new healthcare scheme in India since then has done precisely this and taken away comprehensive primary healthcare by creating silos of schemes and thereby abdicating responsibility towards the Health for All commitment,” says Duggal.

Mathew George, Professor at Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at Central University, Kerala, echoes his views. “Using gig workers as community health workers is not an answer to India’s healthcare woes. It all comes down to how strong the health system is. Where the system functions well, ASHAs perform well; where it is weak, they struggle. The larger issue is the absence of a proper human resource policy for the health system. The challenges faced by ASHAs are really symptoms of that deeper gap. One more parallel workforce is not the solution."

Mathew George, Professor, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Central University, Kerala

He points to the case in Kerala, when ASHAs were added to an already strong cadre of auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), Junior Health Inspectors (JHIs) and Junior Public Health Nurses (JPHNs), duplicating roles and causing considerable confusion. In other states, where there were huge shortages of multipurpose workers (MPW) (frontline community health workers), ASHAs stepped into the vacuum and gradually became the default workforce.

"Over time, credit shifted disproportionately to ASHAs, even though JHI and JPHN cadres continued to do much of the field work, including vector-borne disease control and COVID response."

Evidence consistently shows that ASHAs deliver better where the health system is functional and where caste and communal barriers are low, says George. "The real problem is that we often expect ASHAs to deliver healthcare itself, which was never their mandate. Their training and kits were designed only for limited tasks such as presumptive malaria treatment and ORS distribution,” explains George.

George adds that in difficult-to-reach regions, this could work as a better supply chain for delivery of public health goods, not as health worker in its fullest sense.

"India , like Kenya and Malaysia has similar experience of sending TB test samples and drugs in buses plying in remote areas in Chhattisgarh and Bihar. We have used drones to reach interior areas of tribal and Northeastern regions. Most of it facilitates transport of health goods."

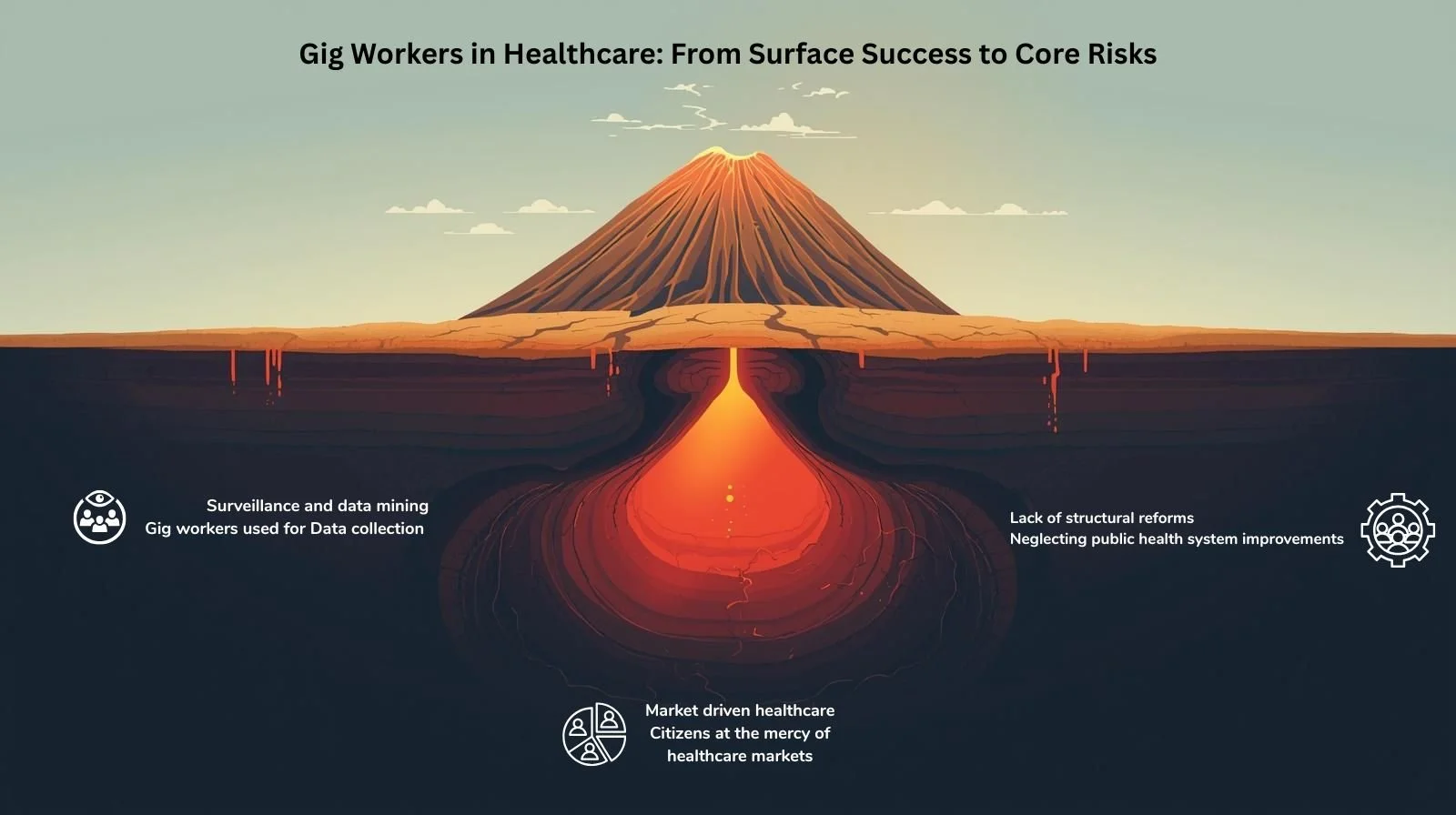

Risks and Privacy Concerns

China’s policy designates some delivery-driver-CHWs as “social supervisors”, something critics say resembles neighbourhood-level surveillance. If India were to adapt any part of this model, the model requires safeguards to protect privacy and build community trust, especially in marginalised urban settlements.

“Even earlier as part of various health programs, there was surveillance. For example, in the DOTS program a third party is supposed to ensure that the patient takes the medicine at the right time, in the right dose. In the Indian context, privacy and data protection of healthcare has become the privilege of the few,” explains Prof Ikbal.

Structural Issues and Exploitation Risks

Dr Sylvia Karpagam is concerned that India is beginning to lay its healthcare system on the shoulders of ASHA workers who have inadequate education, little agency and are the most exploited. “If China’s model works, it would be because of a robust pre-existing health system with a good budget, infrastructure, human resources and other consumables. The human resources are not just doctors but all other personnel like administrators, public health cadre, pharmacists, lab technicians and nurses. Considering gig workers for public health service delivery is similar to feeling proud that we have digital technology. Neither of these will work as a standalone intervention, which is what the government seems to be doing.”

Karpagam also cautions that most of the time, these systems are used to route patients towards an unregulated, city-centric corporate hospital network, making patients spend and leading to fragmented ‘packages’ of healthcare delivery. “Empanelled hospitals, health insurance, public-private partnerships, are all being done to route public funds to private pockets while overtly and covertly dismantling even existing public health systems. ASHA workers and ANMs can only be part of a good system with ambulances, primary, secondary and tertiary health facilities. On their own this system is dysfunctional and these workers are paid the least while expected to pull its weight. Gig workers first need to receive dignified wages with good labour laws. Otherwise they will just be another set of exploited, poorly skilled health workers in a largely dysfunctional healthcare system,” says Karpagam.

Got a story that Healthcare Executive should dig into? Shoot it over to arunima.rajan@hosmac.com—no PR fluff, just solid leads.