What India’s Allied Health Professionals Want the System to Understand

By Arunima Rajan

Does India’s healthcare system treat allied health professionals (AHPs) as essential or expendable?

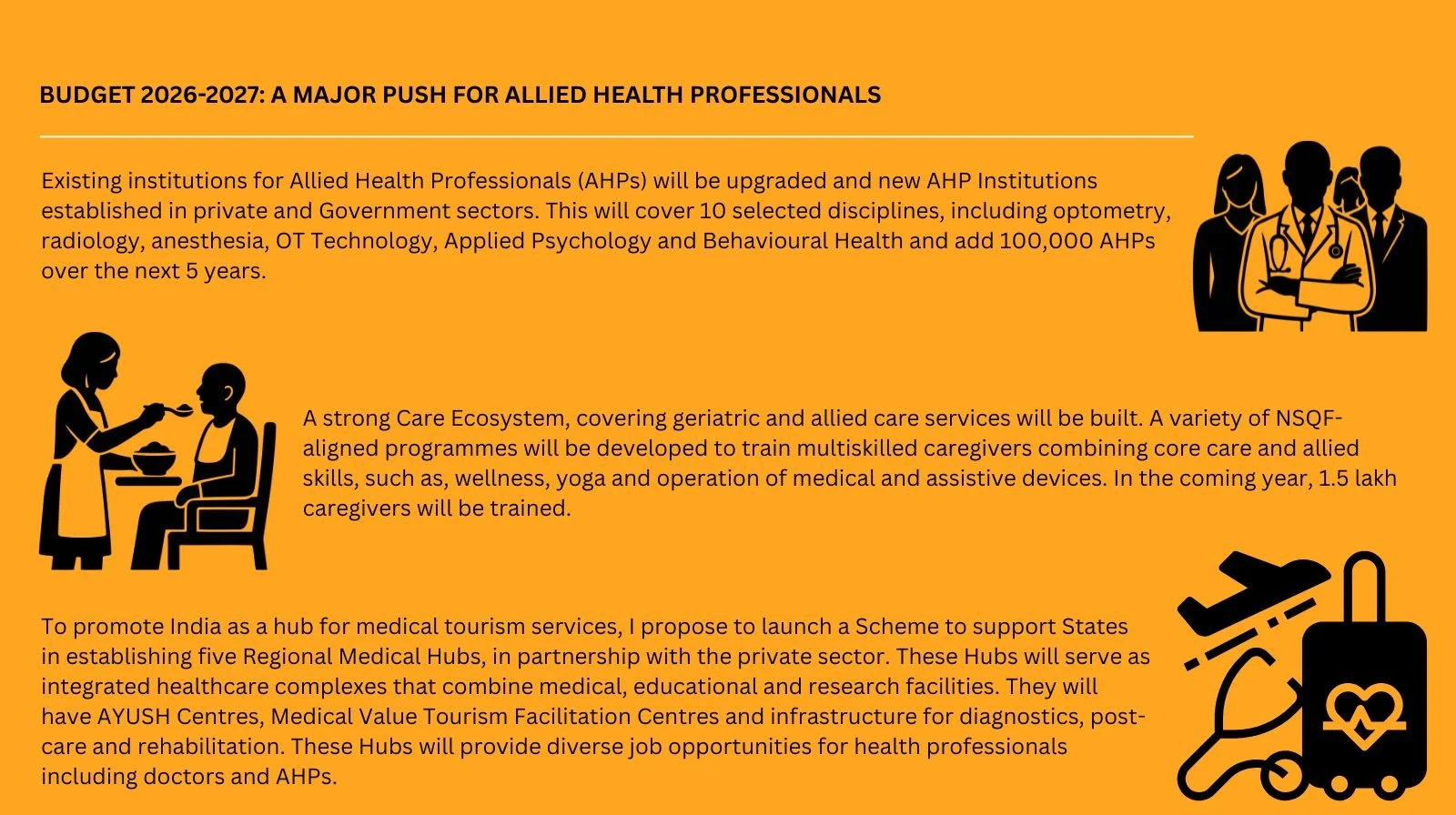

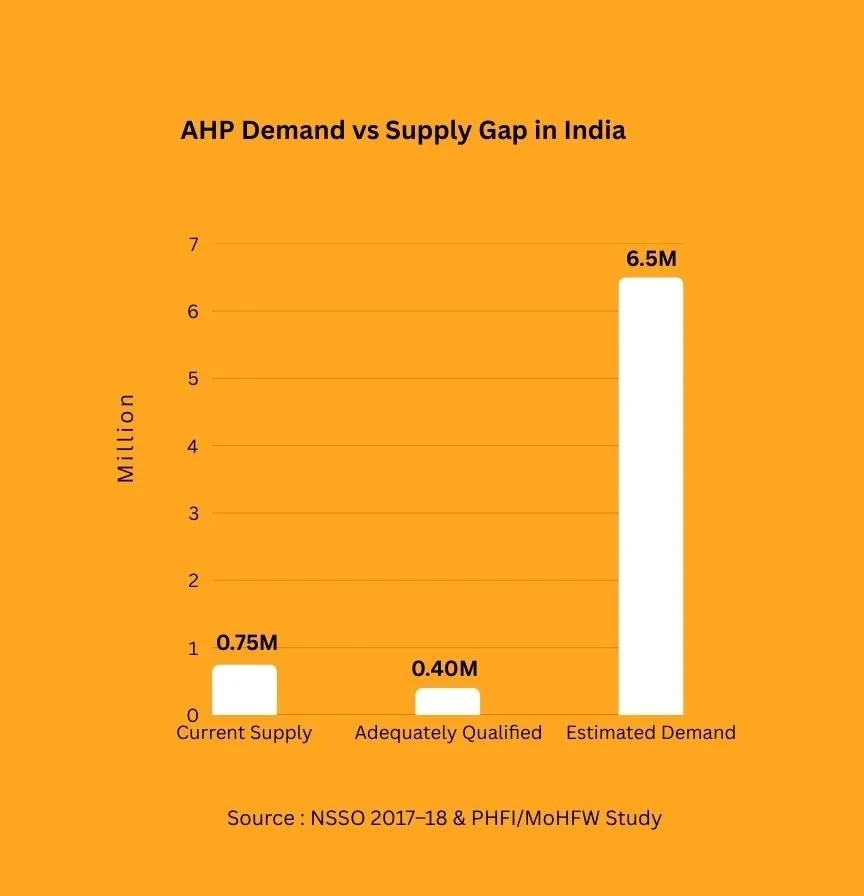

On February 1, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that India would train one lakh allied health professionals over the next five years, spanning 10 disciplines including optometry, radiology, anaesthesia, and behavioural health. The allocation: ₹980 crore for upgrading existing institutes and building new ones, marks one of the most ambitious policy interventions for AHPs since the National Commission for Allied and Healthcare Professions Act was passed in 2021.

Mr. Yoda, a Hyderabad-based preventive healthcare and advanced diagnostics company, welcomed the move. Sudhakar Kancharla, its founder, says the announcement acknowledges a fundamental truth: healthcare cannot scale on technology alone. As diagnostics increasingly rely on AI-driven insights and continuous monitoring, the volume and complexity of information is growing. Translating that complexity into clarity still requires trained professionals.

In preventive care, he notes, the problem is not access to tests but follow-through. That follow-through depends on professionals who can explain results, guide next steps, and build trust over time. In his view, the government’s plan strengthens the human layer of healthcare, the one that turns data into decisions.

A diagnostic report may flag risk, but without a trained professional to explain what it actually means, patients are often left anxious, confused, or in denial. Many delay action or underestimate the seriousness of the findings. This is where allied health professionals become critical. They help patients understand risks, navigate care pathways, and ensure continuity, bridging the gap between early detection and meaningful prevention.

The problem no one talks about

What the budget speech does not address is that India does not lack people training to become AHPs. The real issue is what happens after they enter the workforce.

“There’s no real career progression for most lab technicians,” says Krishna, who works as one in a lab in Kottayam. “I start work at 7 a.m. and earn about ₹8,000 a month. In hospitals, we’re rarely treated with the same respect as doctors. We’re often seen as expendable. The system is built almost entirely around doctors and nurses.”

The protocol gap

“Allied health professionals are often the first point of contact during screening and early assessment,” says Mahesh Makhija, Chairman and Managing Director of QMS Medical Allied Services Ltd. When they are integrated into structured care pathways, with clear protocols, referral mechanisms, and clinical oversight, they can significantly improve access and early detection.

From a patient’s perspective, this integration reduces delays and confusion. Continuity is key: allied professionals must be seamlessly connected to doctors, diagnostics, and follow-up care. When everyone operates within a shared framework, transitions across the healthcare system become smoother.

Makhija adds that delivering technology-enabled care also requires digital confidence. Allied professionals must be trained not just clinically, but technologically.

In preventive care, quality directly shapes patient trust and outcomes. That quality, he argues, must be anchored in defined competency standards, evidence-based protocols, and regular assessments. Meaningful indicators, such as adherence to protocols, screening accuracy, appropriate referrals, and patient experience, should be used to measure performance.

The ones who stay anyway

Despite systemic challenges, many AHPs remain deeply committed to their work. Illangovai Harikrishnan, an optometrist at Maxivision Super Speciality Eye Hospital in Trichy, believes her role is integral to patient care.

She chose optometry because restoring and preserving vision is both clinically significant and personally fulfilling. Her work combines medical expertise with sustained patient interaction, helping people maintain independence and quality of life. She explains eye conditions in simple, non-medical language, describing cataracts as a cloudy lens or glaucoma as gradual optic nerve damage, and often uses regional languages, visual aids, and images to improve understanding.

One of her proudest achievements has been detecting asymptomatic or early-stage eye diseases during routine exams. Early identification allowed timely referrals and treatment, preventing long-term vision loss for many patients.

A battle already fought elsewhere

This struggle is not unique to India. In the United States, where integrated care models are more established, allied health professionals have had to prove their value in similar ways.

“In the early part of my career, behavioural health and other allied roles were often treated as adjuncts rather than essentials,” says Jay Trambadia, a board-certified clinical health psychologist based in Atlanta. While helping build a psychology department within a larger healthcare system, he and his colleagues had to demonstrate value from the ground up, by collecting outcomes data, embedding themselves into medical teams, and showing how behavioural health improved adherence, reduced readmissions, and enhanced patient satisfaction.

As a first-generation Indian American who has spent two decades working in integrative care teams, Trambadia sees in India a problem he has already lived through: a workforce growing faster than the structures designed to support it.

He points out that while fields like physiotherapy, occupational therapy, psychology, speech therapy, and rehabilitation sciences are expanding rapidly in India, career pathways remain inconsistent and training quality varies widely. National credentialing frameworks, standardised regulation, and competency-based training could be transformative.

Embedding allied professionals into interdisciplinary teams early in their training would ensure they are treated as core contributors rather than peripheral providers. International experience shows that integrated teams improve outcomes, but sustaining them requires attention to burnout, fair compensation, psychological safety, and professional recognition. When allied professionals feel supported and respected, they are better positioned to deliver truly patient-centred care.

Essential, yet optional

Nutrition intersects with nearly every hospital ward, yet clinical dietitians are rarely part of daily rounds in Indian hospitals. Rutu Dhodapkar, Deputy Manager of Clinical Dietetics at Hinduja Hospital, Khar, believes formal recognition could change that.

She argues for standardised and regularly updated training pathways, along with a clear career ladder, from trainee to consultant. Hospitals also need better manpower planning, with dietitians embedded across departments to provide timely nutritional interventions.

Research and global practice show that early, integrated nutritional care reduces hospital stays, lowers infection and complication rates, improves healing, speeds recovery, and reduces readmissions in chronic conditions. Nutrition underpins outcomes across the spectrum, from immunity and metabolic control to surgical recovery and cancer care. Recognising clinical nutrition alongside other allied health fields would improve both patient outcomes and public health efficiency.

A commission 75 years late

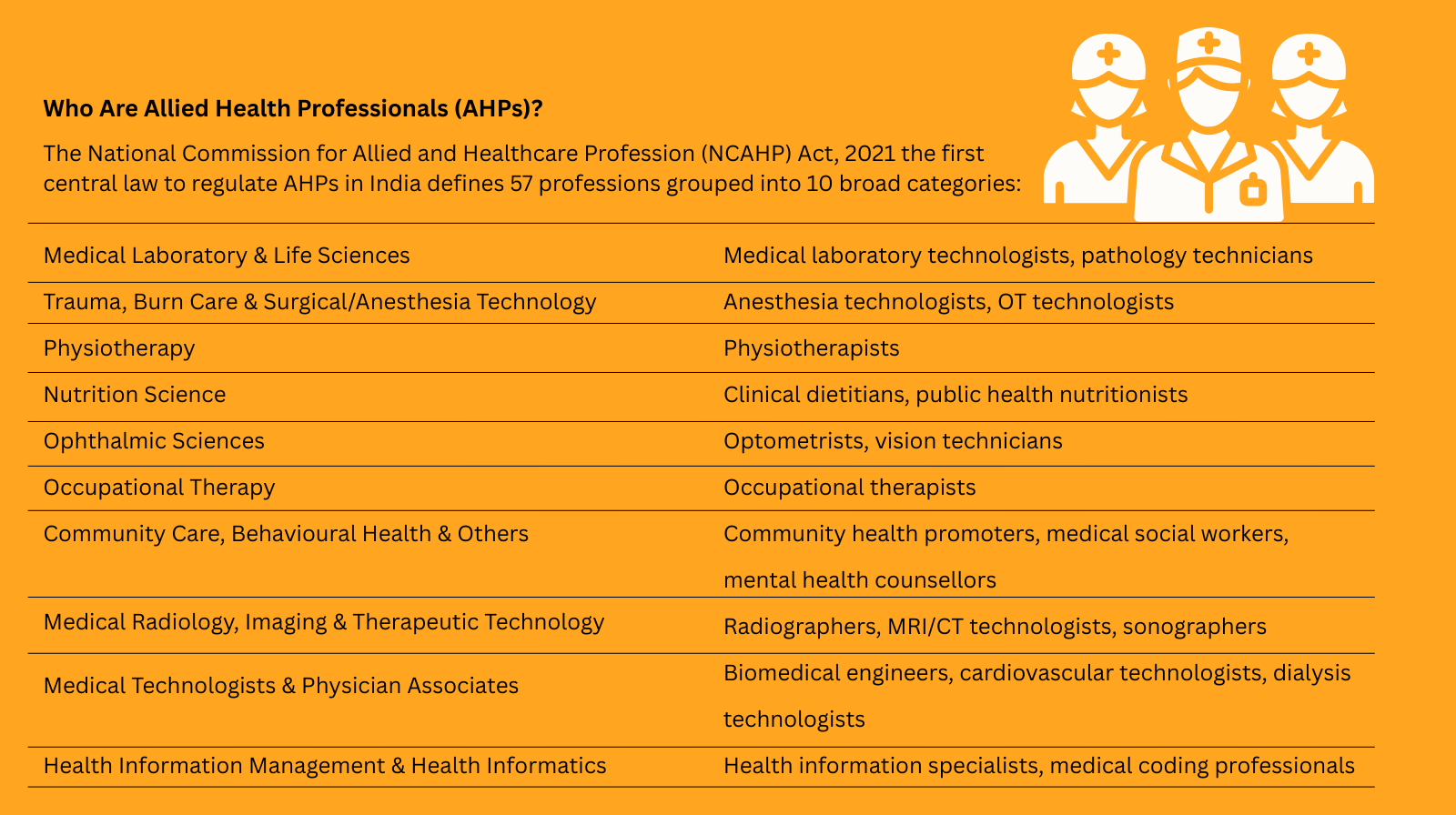

Dr. Girdhar Gyani, Director General of the Association of Healthcare Providers (India), points out that while doctors and nurses have long been regulated by statutory bodies, allied health professionals had no such commission until the National Commission for Allied and Healthcare Professions Act was enacted in 2021.

The Act establishes a National Commission along with professional and state councils to ensure uniform governance. It sets minimum education standards, prescribes curriculum frameworks, mandates institutional recognition across more than 50 allied health categories, and creates national and state registers, making registration mandatory and improving accountability and patient safety.

The Commission was constituted in 2024 and is expected to address long-standing fragmentation in training and certification, which previously varied widely across states. Gyani notes that while some universities offer long-term undergraduate and postgraduate courses, little attention has been paid to entry-level and shop-floor workers. Many general duty assistants, for instance, still enter through labour contractors without formal qualifications, despite being integral to patient care.

The export opportunity no one is pricing in Gyani also sees a global opportunity. With over half its population under 35, India could become a major supplier of certified allied health professionals to healthcare systems worldwide, particularly in developing nations. Proper regulation and certification would not only improve patient safety at home but also create a skilled workforce in high international demand.

For India’s allied health professionals, the question is no longer whether they are essential. It is whether the system is finally ready to treat them that way.

Got a story that Healthcare Executive should dig into? Shoot it over to arunima.rajan@hosmac.com—no PR fluff, just solid leads.